With SUPERMAN RETURNS and THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA winging their way into theaters, aloft on advance praise, there might be hope yet for the most dismal Hollywood summer on record. [I've never skipped so much, ever.] SPIDER-MAN 3 is shooting in my neighborhood, around Smith and Court Sts., so maybe Brooklyn will bring good luck for a better crop next year.

Meanwhile, the independent market is hopping, if only in the number of releases; regarding attendance, they're hobbling. But it would be a shame to relegate THE HIDDEN BLADE (Tartan Films), easily one of the best films of this year (or, for that matter, 2004, when it was released in Japan), to your Netflix queue.

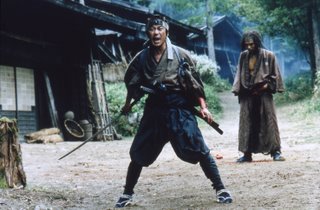

As it happens, I saw it on a screener DVD. Impressive there, I can only imagine how much more I'd be taken with it at a theater. Since Film Forum of New York's dazzling "Summer Samurai" series last year I've gone a little samurai-happy; SAMURAI REBELLION, the cornerstone of that festival (now on DVD from Criterion) was a sensational film, and I've seen several since. THE HIDDEN BLADE is kith and kin to the very best recent samurai film, no, not the pre-breakdown Tom Cruise's LAST SAMURAI, but 2002's THE TWILIGHT SAMURAI, an international hit that received a subsequent release here. At age 71, its writer-director, Yoji Yamada, was an overnight sensation, and THE TWILIGHT SAMURAI, which swept the Awards of the Japanese Academy, went on to receive a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar nomination in 2004.

Yamada was hardly an unknown quantity; indeed, his stewardship of the wildly popular Tora-san films, detailing the gentle misadventures of an ordinary salesman, made him one of the country's most successful directors. But samurai travel better than salarymen. I've not seen a Tora-san film, but the qualities ascribed to them--their quiet, becoming modesty, credible, character-based humor, and affection for individuals stuck at the bottom rungs of society's ladder--were surely the reasons the two otherwise very different samurai movies have met with so much success. It's not their wall-to-wall action; samurai film fans know that the best of these films are coiled tight, with the screws turning subtly throughout, till the final, explosive release. The blade in THE HIDDEN BLADE is hidden for so long you may well forget about it, but when it's finally, devastatingly drawn, look out.

THE HIDDEN BLADE stars Masatoshi Nagase, who you may remember as one of the Elvis-struck Memphis visitors in Jim Jarmusch's MYSTERY TRAIN (1989). Nagase has played a comical detective in a popular movie series since then, and I was surprised to see how well the 19th century samurai code fit him after so much onscreen slacking off. His character, Munezo Katagiri, has sharp instincts undulled from the onset of middle age, but his loyalty to the code is doubly tested, when his clan obligates him to kill a trouble-making older comrade, and when his secret love for a former housekeeper, Kie (actress and pop star Takako Matsu, warmly sympathetic), is severely tested.

The mood, which grows ever more taut over the course of the film's exceedingly well-paced 132 minutes, is splendidly sustained, as one man's allegiance to all he holds sacred begins to waver in the face of changing mores. There are, for example, some funny scenes involving a changeover to Western-style artillery, handled more offhandedly than in the Cruise film. What's smartest about THE HIDDEN BLADE is its economy of production, which is just the right size and convincingly, not overelaborately detailed, and austerity of emotion. Nothing is wasted; everything is conserved, and purposeful, as the film moves inexorably to its conclusion. It's a gem, heartily recommended. And, more good news, Yamada, 75 this year, is making another samurai film.

A picture is worth a thousand words, so the moving pictures of THE ROAD TO GUANTANAMO (Roadside Attractions) must be priceless. It's one thing to read about the sorry state of affairs at this outpost of the "war on terror"; another to see still photos; and quite another entirely to see the confinement and imprisonment enacted, documentary-style. Even this modest photo is unsettling, like something from a sci-fi film, suggesting captivity on Mars. But it's going on in the here and now, in Cuba, with no end in sight as a black mark against the American and British allies continues to widen, like a stain.

The film dramatizes the odyssey of the "Tipton Three," British citizens who, while attending a wedding in Pakistan, crossed into Afghanistan to deliver humanitarian aid as the U.S. began bombing the Taliban. The action is conveyed matter-of-factly, in the manner of co-director Michael Winterbottom's harrowing immigrant saga IN THIS WORLD, and intercut with comments from the actual men. Missing, however, is the rationale, the specifics, of what drew these young, Gap- and Adidas-clad men into the vortex of war in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and the matter of their past brushes with the law is briskly eluded. Lacking context (the film, co-directed by Mat Whitecross, has no credited screenwriter), I couldn't help but feel that these men were guilty of something, if only incredibly bad judgment as what can be seen one good thing to come out of the war to date (the dismantling of the wretched Taliban regime) came to pass before their eyes.

Were they collaborators? Terrorists-in-the-making? Unclear. But did their punishment, meted out once they were captured by Northern Alliance forces and locked in metal containers, then sent onto the Guantanamo camps for two years without charges, fit the crime? Clearly not, argue the filmmakers, and their evidence is persuasive. This is not the glamorous, James Bond-like fortress Gitmo of BAD BOYS 2, or even the more by-the-book A FEW GOOD MEN, but a squalid, grubby place, where the prisoners are confined in outdoor cages and routine torture and interrogation is the norm, and the only tender mercy is when an officer snuffs out a tarantula that has sneaked into a cell. That, and a surrealistic celebration that breaks out when the young men, nearing the light at the end of a very long tunnel, are treated to Pizza Hut and McDonald's by their captors.

The cinema verite work by the cast and crew, led by the inexhaustible Winterbottom (six films, different from one another, in three years), is nothing sort of astonishing. You are there, in the shoes of the reenactors, in Pakistan and Afghanistan, as their story develops. (Filming also took place in Iran, where Gitmo was recreated--read into that what you'd like.) It's satisfying on a purely physical level, however insufficiently the drama is developed. (IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER may the best attempt to make a film of this type without the trappings of documentary.)The second half of the 95-minute film is a seemingly endless round of badgering, dirty tricks, and abuse, that you'd like to turn away from.

But don't, whatever questions you might have about what brought Asif, Shafiq, and Ruhel into this heart of darkness in the first place. Is this ROAD where a truly national conversation, beyond the bullet points and talking heads, about Gitmo begins? I'd like to think so, but that will mean commitment on the part of Roadside to ensure adequate distribution and a filmgoing public willing to engage it.

When did movie comedy get so ugly to look at? It wasn't always so; the Hollywood classics had that sheen to them, and a Blake Edwards in his prime could be counted on for a crisp widescreen image. But standards have been lax for some time; so many comedies have a cheap, dimly lit, disreputable look about them. Is it the cheap, disreputable content--has anything with Ben Stiller been artfully composed? I'm sure STRANGERS WITH CANDY (Thinkfilm, opens June 28), an extremely modest expansion of the funny Comedy Central show, was made on an extremely modest budget, but shooting in the less leafy precincts of the Garden State is no excuse for the crap look of the movie. The film seems to have been shot with the less demanding home video market in mind, which is the best place to see it, with a case of Bud close at hand.

I liked the show, which gave the prosthetics-loving Amy Sedaris a place to shine. She played Jerri Blank, a 46-year-old reprobate who decided to change her fate by dropping back into high school, leading to skewed life lessons along the lines of ABC's "Afterschool Specials" for teens. At the end of the series, students and teachers alike revolted and destroyed the school, which rather ruled out a movie sequel. So the film goes back to the beginning, which obliges it to rework the less amusing material about Jerri's fractured home life that got the program off to a false start (it didn't hit its stride until its second season).

The regulars, who besides Sedaris included Stephen Colbert in another pompous portrayal and Paul Dinello as hopelessly closeted teachers, are back on duty and are all OK, but just OK--their co-written script, which has Jerri trying to win a science fair to revive her dad from a coma, isn't as fresh, or as sharp, as the best of the shows. And I'll bet the zomboid, unfunny guest stars, who include Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ian Holm, Matthew Broderick, and Sarah Jessica Parker, were probably hoping that the film, whose release was delayed, would have stayed on the shelf a little longer, or shuffled off quietly to pay cable. At 87 minutes, it's nothing to get too worked up about, but it dragged, which I was not expecting; you can easily devour three of the half-hour shows without looking at your watch. And Dinello's low-energy direction, coupled with the low-wattage lighting, had me wishing I had hooked the screening.

Here's a few long-ago laughs with Sedaris.

Grendelmania is upon us. Next month's Lincoln Center Festival showcases Eliot Goldenthal's opera GRENDEL, from the John Gardner novel, with puppety direction from his wife and collaborator Julie Taymor. Robert Zemeckis is putting the CGI expressiveness of his POLAR EXPRESS to work on a another version of the great Anglo-Saxon poem of the warrior and the beast, BEOWULF, due next Christmas.

But first, BEOWULF & GRENDEL (Union Station Media/Truly Indie, opens July 7), a Canadian-Icelandic co-production with the right stuff when it comes to harsh, unforgiving locations--but wrong, wrong, wrong everywhere else. Lacking other sources, I sometimes use Variety reviews as a guide to whether a film is worth scheduling, and the one this film got indicated trouble ahead. But I like the story, and it's got a monster, so, why not?

Well, for openers, Gerard Butler and Stellan Skarsgard, cast as Beowulf and the king who employs him to rout the trouble-making Grendel, have accents thicker than their broadswords; this is an English-language film that requires subtitles. Sarah Polley, uncomfortably cast as a whore-witch, wears a terrible red fright wig. Ingvar Sigurdsson's grunting Grendel is a bore. The production is threadbare, which may reflect historical accuracy or a financier who fled to Monaco with the budget. The "contemporized" language ("this troll is one tough prick!") caused ripples of laughter as the screening room audience mostly dozed. And the director, Sturla Gunnarsson, kept the camera locked into one or two positions, as if it froze in the mud and couldn't be moved. I've never seen a movie more lifelessly composed. It's not even up to the low standards of Sci-Fi Channel movies where boas fight pythons.

And the screening was at 10 am. On a Monday. What was I thinking?

No comments:

Post a Comment